My Struggle with Identity in a White Education System

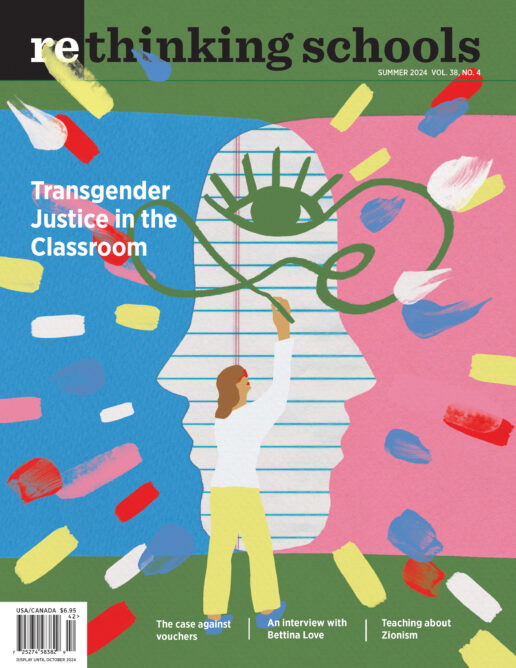

Illustrator: Howard Barry

At least 18 states in the past few years have banned or restricted critical approaches to teaching about race and racism, allegedly to “protect” white children from any discomfort that might come from facing racial realities. But those same lawmakers seem to have no concern with the damage done to Black children by teaching that distorts or denies those realities.

For me, this debate is personal, not just intellectual and political. My experience in public schools left me feeling betrayed and angry, instilling a nagging inferiority complex that led me to lose interest in education, one of the factors that pushed me into the school-to-prison pipeline.

I was in school from 1991 to 2004, a time when many felt that the promise of the civil rights movement was not being realized fast enough. Today, I fear the problem is not the slow pace of forward movement but a country going in reverse. I fear that the censorship of critical race theory, and Black studies more generally, will not only leave white students badly educated about racism but will undermine the self-esteem and limit the potential of many non-white students, especially Black children.

It’s more important than ever that we Black people fight for the right of all students to know the truth.

Let’s go back to those new state laws. Perhaps most notorious was Florida’s 2022 Stop WOKE (Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees) Act, which outlaws teaching that produces “guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress because of actions, in which the individual played no part, committed in the past by other members of the same race, color, sex, or national origin.”

No one wants to blame slavery on white schoolchildren, of course. But the law’s goal is misguided, because discomfort can be a good thing, a sign that one is letting go of soothing stories to grapple with terrible truths. I know this from experience — as a man, it has often been distressing when I have faced a feminist critique of male dominance and had to come to terms with my own sexist behavior. White people should not fear such discomfort, which can be a sign of intellectual and moral growth.

But my focus here is on how a fear of facing white supremacy — both in U.S. history and in contemporary life — affects Black youth. My life is an example of the potential harm.

Looking back, my 5th-grade year in the Tacoma public school system — the year I learned that I was a descendant of enslaved people — was one of the most critical times in my life. At the age of 10, I got my first school lessons about racism in this country, but unfortunately those lessons were inadequate.

My favorite subject that year was history. I remember being in awe as we heard the story of Christopher Columbus, read the Declaration of Independence, learned about how the forefathers of this country fought against the tyranny of the British Empire in the Revolutionary War, and studied the Constitution. I stood each morning with pride as I placed my right hand over my heart and pledged allegiance to the flag that so many fought and died for, believing that all men were created equal. My stepfather had been in the military until I was 6 years old, and so I had been taught patriotic values, growing up on a military base around a variety of people. At the end of that section of our history curriculum, we watched The Patriot, and that day I raced home to beg my mom to buy that Revolutionary War film for me. She couldn’t afford it, but she did rent it and I watched it every day until she had to return it.

I was an all-American boy who believed in the all-American story. I was enthralled by a captivating tale of freedom won through rebellion and revolution, identifying with the struggle of the oppressed even before I understood why. But later that year, I would learn that the country I believed in and loved so much didn’t love me back the same way. Only then did I start to understand why the struggle for freedom against oppression resonated so deeply in me.

I remember the day our study of the Civil War began, when I started to learn about the barbaric treatment of enslaved Black people. That was the first time I began to take notice of the power dynamics between Black and white. My 5th-grade history book told me that Abraham Lincoln’s mission was to “free slaves,” for which he ultimately was killed — the hero of the story was a white man. The book had pictures of those enslaved Black people working in fields picking cotton, with white men on horseback carrying guns and whips while the enslaved, dressed in tattered clothing, worked tirelessly under the hot sun. I saw pictures of men, women, and children who looked like me being whipped by white plantation owners. When we finished that chapter, we watched the first half of the TV series Roots, which traumatized me more.

I needed to understand this brutality but found no answer in the textbook, which seemed focused on the virtues of the white men who fought and died so that Black people could enjoy the freedoms we have today. I asked my teacher how all this could happen, looking for an explanation of the cruelty, but her only response was that was just the way things were back then. I looked around the classroom at the other Black kids, but at that age we had no way to help each other understand.

That day I ran home in tears, as my pride in this country began to disappear, and the hurt I felt inside began to turn into rage.

My ancestors were depicted as mere shells of human beings, their only hope coming from benevolent white people.

I was waking up to the reality of who I was as a Black boy in the United States. As James Baldwin so eloquently said in 1961, and which is still true today, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time.” I was learning about the strength and courage of all of these white men while my ancestors were depicted as mere shells of human beings, their only hope coming from benevolent white people.

I often wonder what was going through the minds of my white classmates. Did they feel the same horror that I felt? Or did they feel pride witnessing the power held by those who looked like them? Whether white men were the “good guys” or the “bad guys” in that history, they were powerful. What would my classmates have felt if the roles were reversed and the textbook was full of pictures of Black men on horseback with guns and whips controlling subjugated white people?

I wanted to escape from the history of racism and anti-Blackness in my country, to identify with Black strength and accomplishment. It wasn’t until Black History Month later that year that I learned about 19th-century heroes such as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, and the 20th-century civil rights movement activists Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. I was finally able to see Black people who stood up to the evils of slavery and segregation. But these were about the only Black people mentioned, and they were presented as minor characters in the great American story.

Neither textbooks nor teachers were much help in answering my questions. If the Civil War had set us free, what was the civil rights movement fighting against? The answer was racism, but where did it come from? Our teacher taught us that racism was the result of Southern rage at losing a war and losing “their slaves,” but that after the Civil Rights Act was signed and MLK was murdered, racism was pretty much over. I was taught that we now lived in a color-blind country, a melting pot of ethnic diversity, a desegregated world in which I enjoyed the same freedoms as everyone else.

But my experience suggested that wasn’t true. If racism was no longer a problem, why did I feel trapped by an identity that seemed to put me in a position different from my white classmates? Not every white student was thriving, of course, but why did most of them seem to have a confidence that I lacked? Why did it seem that people treated me differently than white kids, expecting so little from me and with so little faith in my potential? No matter how much I tried to excel and rise above it all, why did it sometimes seem that all my efforts were for nothing?

I realize now that I was being “educated” to accept a lie. I did not know how deeply racism was still woven into the fabric of every system in this country, including the schools. The way I was educated created mistrust and insecurity in me as a Black person. As a child, I felt powerless and at times I still do.

How would my life have been different if I had learned about Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and other prosperous Black communities in U.S. history? I didn’t learn about Black inventors and explorers, or about Black civilizations before the Atlantic slave trade. My history books not only downplayed white barbarism and Black suffering by avoiding subjects such as the murder of Emmett Till or the extent of lynching, but they also mostly ignored Black accomplishments.

I’m not in prison solely because of textbooks and teachers, of course. But my disconnection from school is part of the story. And it’s ironic that I didn’t begin to learn anything of importance about race and racism until I came to prison. I have learned more about myself through the underground political education that occurs in prison yards, chow halls, and day rooms — supplemented by a few college courses and lots of reading in the prison library — than I ever learned in the public education system. I have read about the pseudoscience that long justified white supremacy, about how violence and public policies disempowered Black people economically and politically. I also learned about the connection of Black people in the United States to the peoples of Africa. In prison, I began to more fully understand oppression, how powerful people dehumanize others to justify barbaric treatment and exploitation.

In that one fateful year of grade school, the excitement I felt about learning was replaced with anger, confusion, and frustration. I started the 6th grade feeling disconnected from my education. I couldn’t see much value in what I was being taught, in part because it so rarely seemed to connect to my life. I am not the only Black person with this experience, but the school system either didn’t notice or didn’t care. Like so many other Black children, I was just pushed through the system until I was pushed out.

I don’t tell the story of my experience to make white people suffer. All I ask of white people is to realize how a sanitized story about America both deprives their children of the knowledge they need and puts Black children at greater risk of despair.